SOUL BOWL ’70

The story behind the show

by Theo Mitchell

Imagine this. Your favorite artists. An incredible lineup jam-packed in one night. All happening right in front of your eyes and on the 50-yard line of your college campus stadium.

This was the exact case one fall evening in Uptown over 50 years ago. On October 24, 1970, Tulane University played host to a show that could easily go down in history as one of the most star-studded collectives ever assembled.

Ladies and gentlemen, this is Soul Bowl ʼ70.

James Brown: Mr. Dynamite. Courtesy of Alan Leeds, Jambalaya 1971.

The reality of thinking back to over 50 years ago, in the United States, can bring many to see some stark similarities between then and now. With the sixties turning into the seventies, the hope of the new decade was to leave any form of turbulence behind.

Tulane Football even dubbed 1970 as the “Year of the Green” for its expected team success on the gridiron.* However, no sports victory could fully distract communities from significant matters impacting all Americans. From social tensions and rising movements for change to controversies in leadership and international affairs, all institutions met these forces head on and Tulane was no exception.

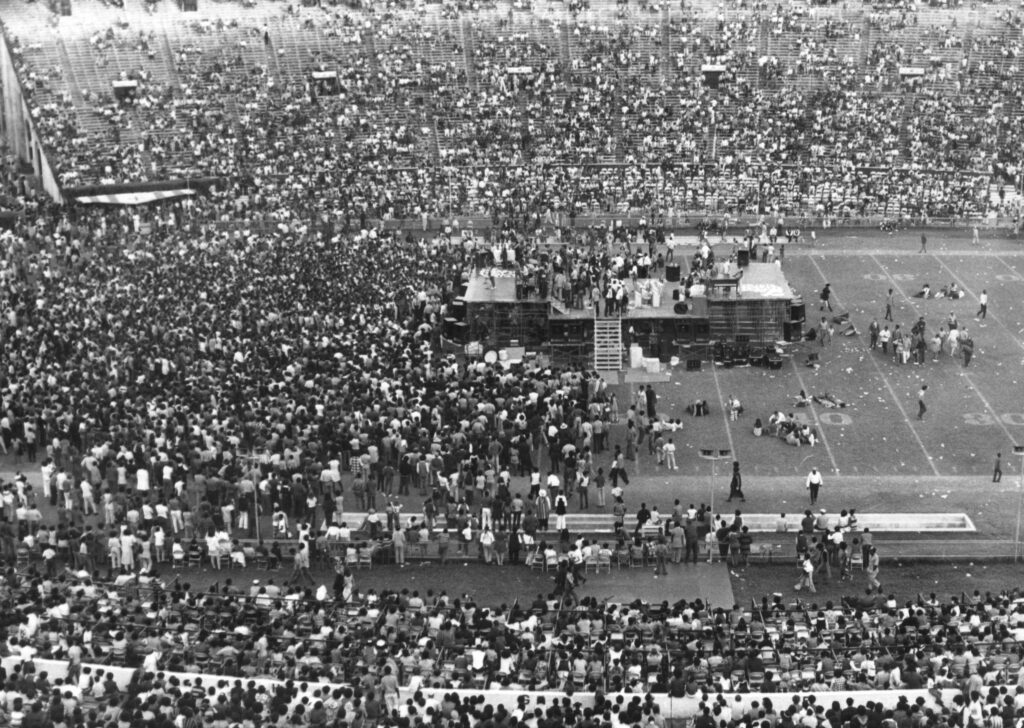

Over 25,000 strong to witness an evening of soul. Courtesy of University Archives, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University.

Over 25,000 strong to witness an evening of soul. Courtesy of University Archives, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University.

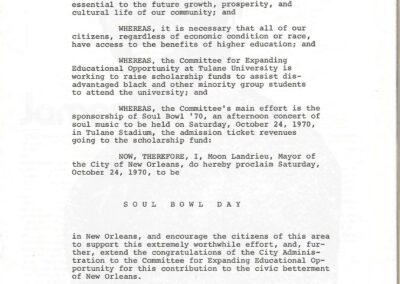

As the university was navigating these challenges, an obstacle that also stood tall for Tulane was the expiration of the Rockefeller grant in 1970. Scholarship funds of $500,000, provided by the Rockefeller Foundation, played a vital role in Tulane financially supporting and admitting more students of color starting in 1964.

The increased admission of students of color along with their achievement in the classroom helped Tulane to not only become more of an academic powerhouse but also a more culturally enriched environment. Despite the success of this effort, the grant was not intended to be a long-term solution.

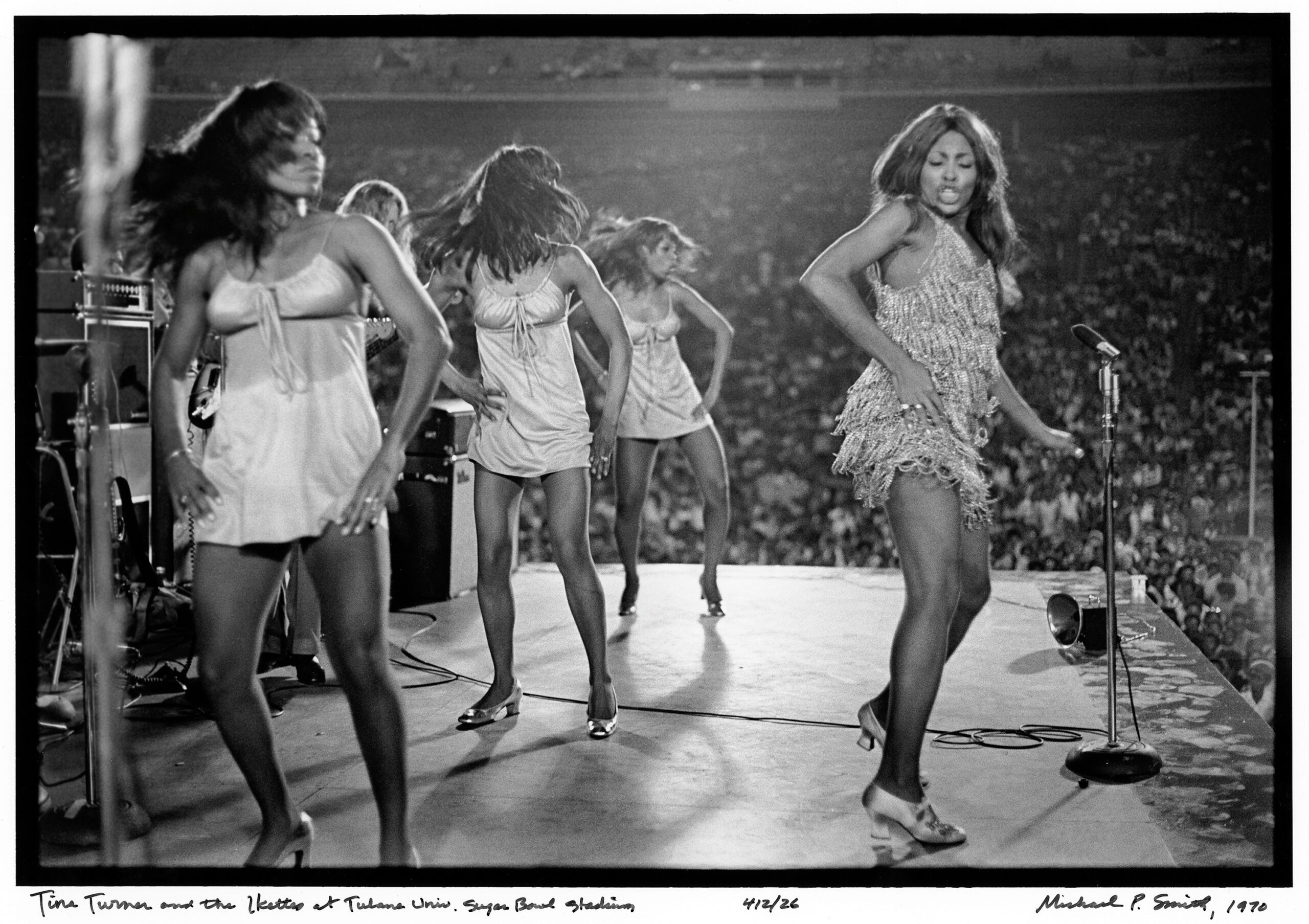

Tina Turner and the Ikettes: a master at work. Courtesy of Michael P. Smith/Historic New Orleans Collection.

Funds from the grant would be fully utilized by the time students graduated in 1973, and Black Tulane students were highly concerned that more solutions of new revenue streams were not being solidified in time.

Although then-Tulane President Herbert E. Longenecker promised the community that plans were in progress for more funding, various Tulanians jumped into action to immediately.

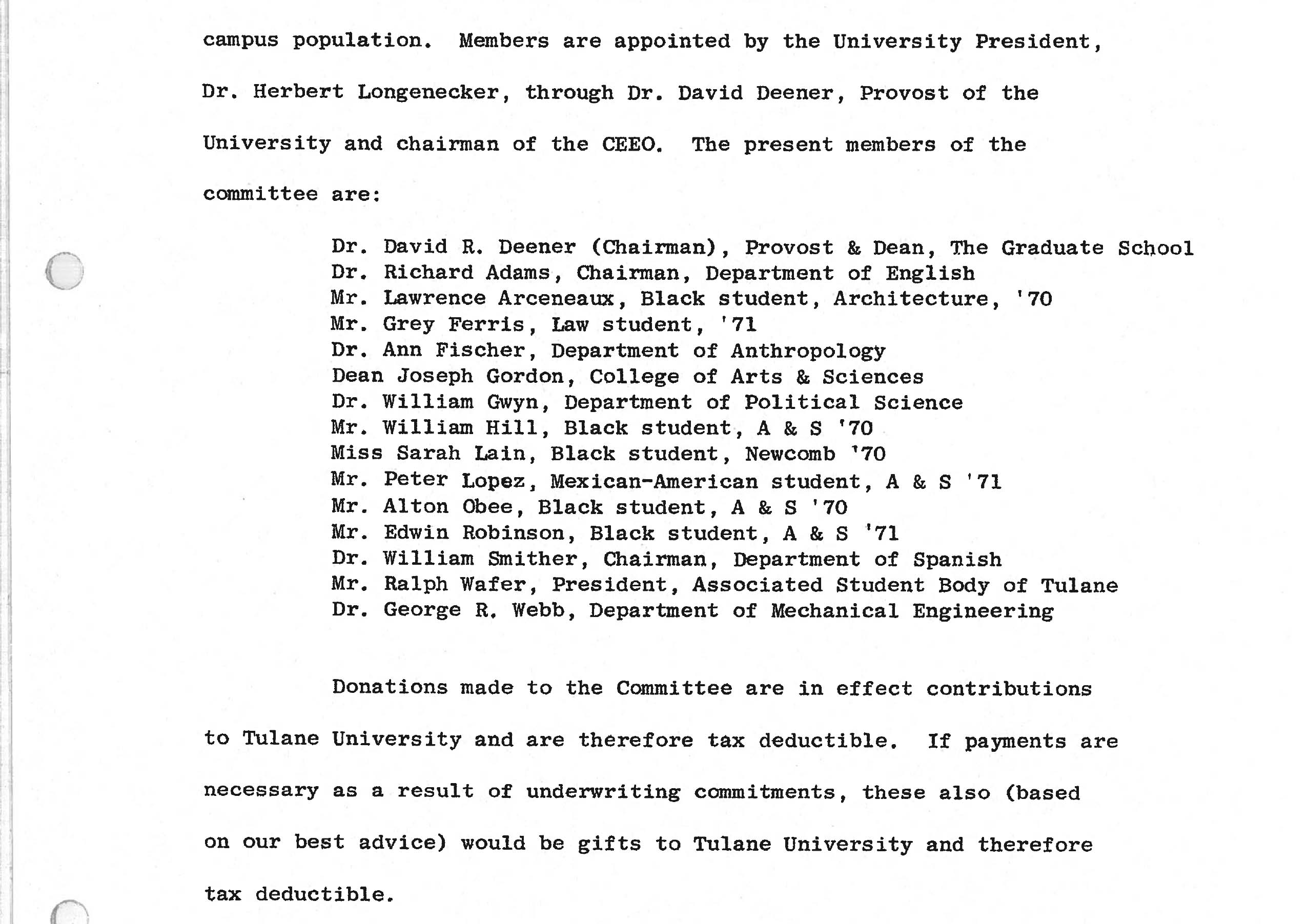

As a result, the Committee on Expanding Educational Opportunity (CEEO) was formed in 1969, led by Dr. David R. Deener, provost and dean of the Graduate School, and an initial campaign was established that raised over $15,000.

The campaign ensured that students were covered for the 1970-1971 academic year and that the university would continue to admit students of color at the same rate as previous years. But, the campaign also made it clear that larger sums of money through bigger mediums were needed to maintain any momentum. Fortunately, through the imagination of students within the CEEO, a much bigger medium was conceived: Soul Bowl ʼ70.

List of CEEO members: the team responsible for delivering Soul Bowl ’70 to music fans, Tulane University, and the city of New Orleans. Courtesy of University Archives, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University.

The CEEO understood from the start that Soul Bowl ʼ70 would not be the ultimate, end-all solution. However, the team truly believed that the concert could bring two elements to the forefront: establishing greater financial support and a bridge between a predominately white institution and a Black city, especially its youth. The CEEO shot for the stars in how they envisioned the show and its goal of raising $250,000 in scholarship funds.

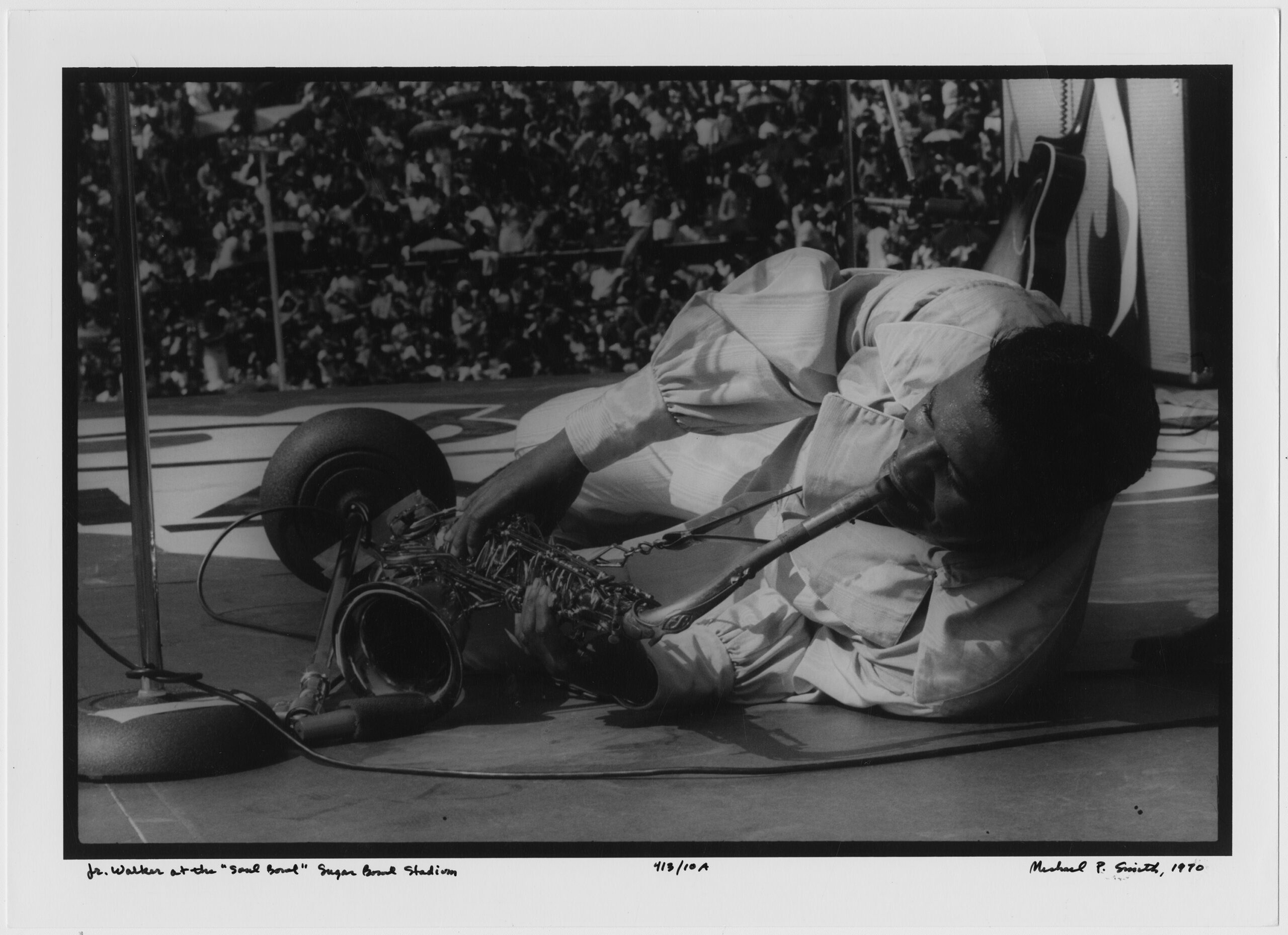

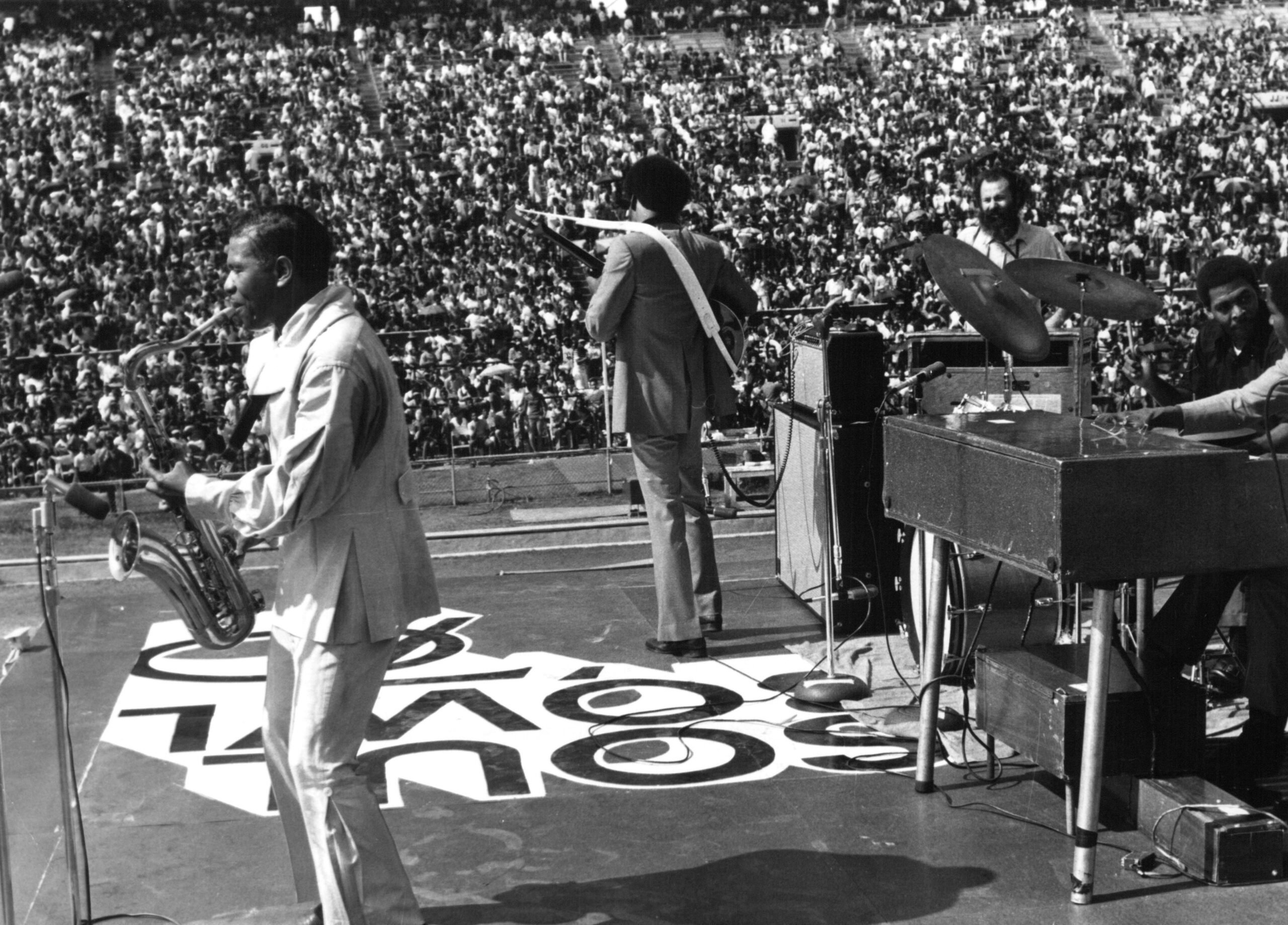

The emphasis on soul, instead of rock, was a key factor for the CEEO as they wanted to drive home how this style of music, its influential fanfare, and a genuine cause could bring 50,000-plus to Tulane Stadium. The plan was to deliver a full house grooving for six hours to a whoʼs-who of chart-topping artists, genre-bending talent, and future rock-and-roll hall of fame legends. The lineup featured Jr. Walker and the All Stars, Rare Earth, Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E), the Ike & Tina Turner Revue, Isaac Hayes, and James Brown.

The lineup raised eyebrows and perked interest from music lovers both near and far. But, the biggest hurdle in delivering the show was its own production costs. The CEEO and Tulane University officials both agreed that an underwriting of $150,000 was needed to protect stakeholders from any financial losses. Tulane stepped in and agreed to provide $50,000 of underwriting if the CEEO could locate the remaining $100,000.

Locating $100,000 was a daunting task for the CEEO, and it led to the postponement of the show twice. But, the CEEO and its students prevailed, located funding, and secured its October 24 event date by partnering with various white and Black businesses, public officials, and civic leaders of New Orleans. Furthermore, the CEEO also relied on members of the Tulane community – fellow students, faculty, staff, and alumni – to ensure that funding was solidified and that the show would certainly go on.

Staff Pass: Access granted. Courtesy of Alan Leeds.

Excitement was undoubtedly in the air for showtime, but the day also brought along setbacks – both expected and unexpected. The start of the show was delayed, leaving concertgoers baking under the sun. In addition, rumors were spread that Soul Bowl would turn into a race riot, which scared away more potential attendees from Tulane Stadium.

But, staying in tune with the nature of soul music, the crowd stayed cool until the show opened an hour later with Jr. Walker and the All-Stars then followed by PG&E and Rare Earth. Despite experiencing great success on the charts in 1970 with their version of “Get Ready,” Rare Earth, along with PG&E, both received a lukewarm reception from the predominantly Black audience.

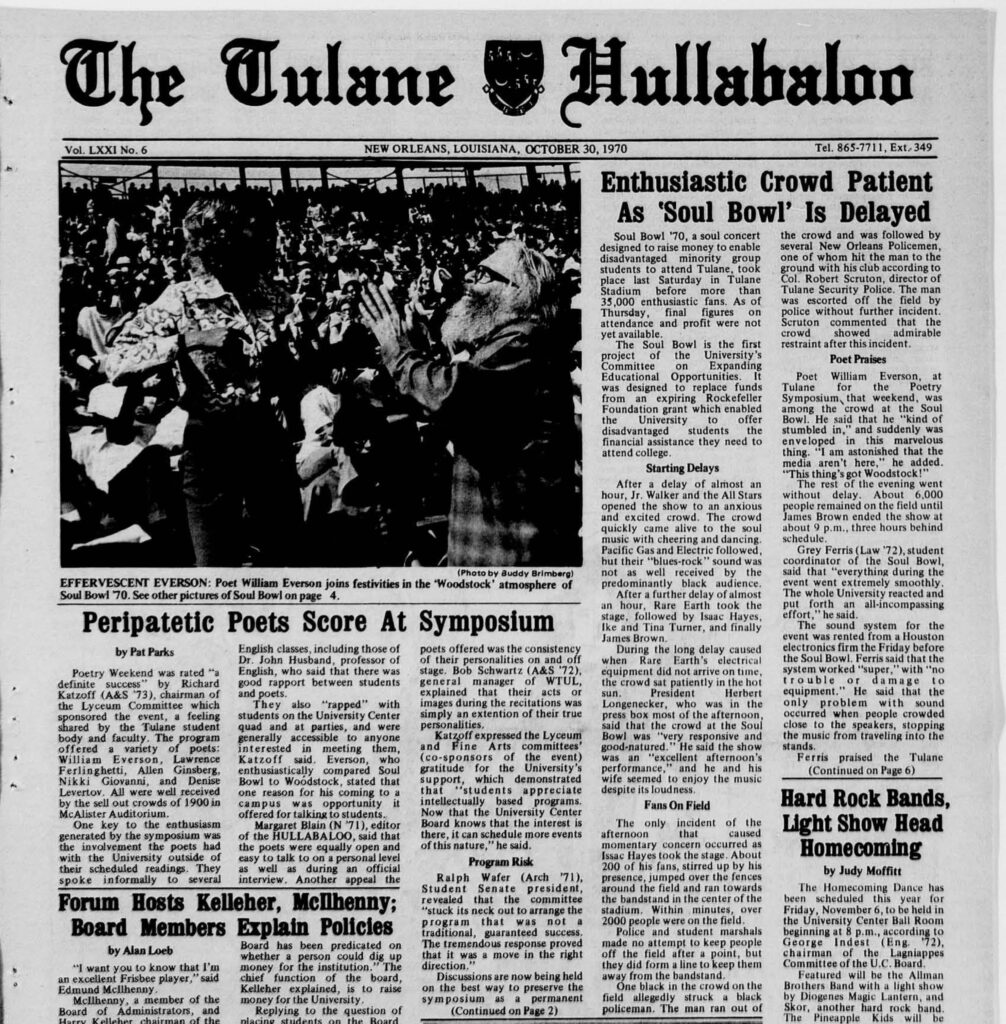

A concert review, from both the October 30, 1970 edition of The Tulane Hullabaloo and the publication Down Beat, claimed that both acts – groups consisting of both Black and white members – were not well received by the audience and were only included in Soul Bowl ʼ70 to leverage their pop chart success into more white supporters and faces in the crowd.

The team truly believed that the concert could bring two elements to the forefront: establishing greater financial support and a bridge between a predominately white institution and a Black city, especially its youth.

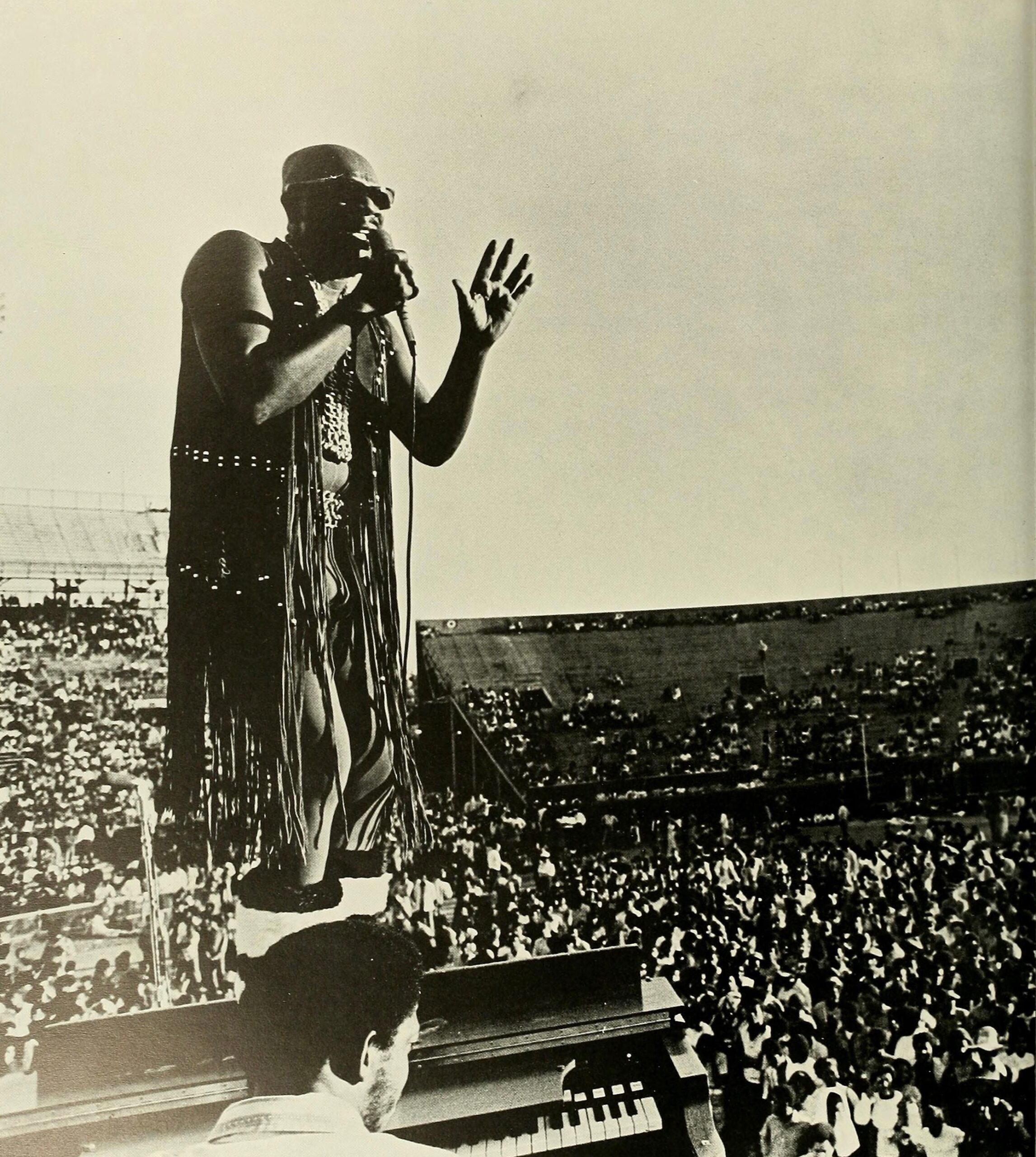

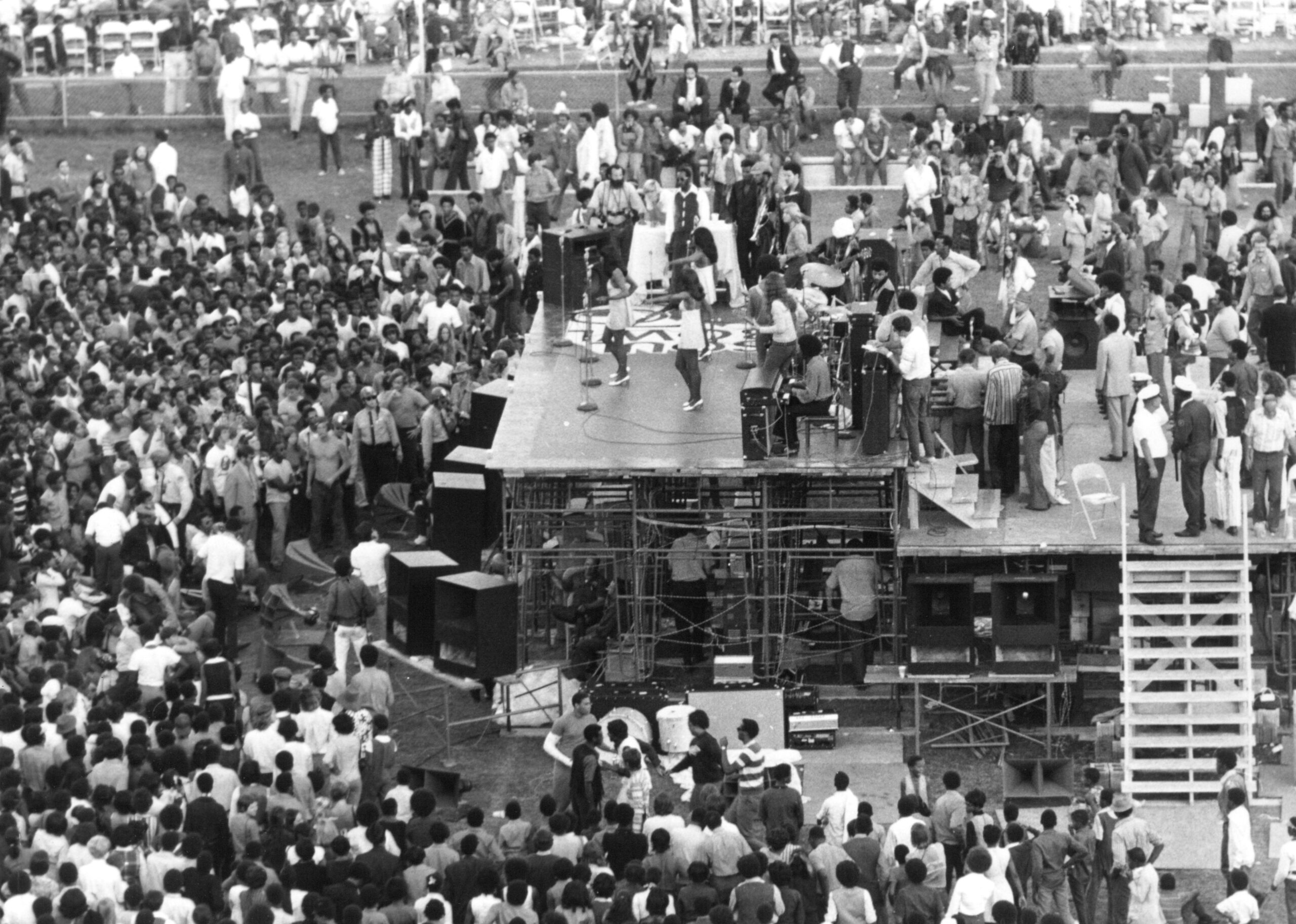

Nevertheless, attention and admiration from the crowd skyrocketed with the introduction of the man once called “Black Moses.” Accompanied by a 21-piece band, consisting of members from the New Orleans Symphony, Isaac Hayes took the stage to pure adulation.

The crowd became unglued and rushed the stage. The organizers had hoped guests would stay in their bleacher seats throughout the show, and urged the audience to return to their original seats and stop blocking the speakers.

Isaac Hayes: The maestro from Memphis. Courtesy of Jambalaya 1971.

The police and security initially tried to keep fans away. But, the fans were too enamored with Hayes and his offerings to truly leave the field, and both the police and security eased up on their restrictions. Once Hayes finished his set with a shortened version of “I Stand Accused,” the show elevated to another level of positive momentum with the arrival of the Ike and Tina Turner Revue.

“What You See is What You Get” was the first number of the set, but the title alone was a complete understatement to the stage presence presented by the Ike and Tina Turner Revue. The Turner collective brought a frenzy to New Orleans that truly delighted the crowd. Backed by Ike on guitar and their signature background dancing trio, the Ikettes, Tina owned the stage with a prowess that kept the audience following their every move and groove.

Ripping through classics like “What Do You Like?,” “Honky Tonk Woman,” and the timeless “Proud Mary,” the crowd was watching a master at work in Tina. The Turner collective had Tulane Stadium in their hands and didnʼt ease up on their grip as they approached their closing number, “I Want to Take You Higher.” Their Sly & the Family Stone remake not only kept the crowd on their toes but also anxiously awaiting the closing act – James Brown.

Jr. Walker giving the Soul Bowl ’70 crowd all he got on the saxophone. Courtesy of Michael P. Smith/Historic New Orleans Collection.

A major concern stood at the core of the showʼs last delay: with fans clamoring for Brown. How do you safely transport Soul Brother #1 from the dressing room to the stage?

The wait was worth the visual that added to the legend of both Soul Bowl ʼ70 and the “Godfather of Soul.” After back-and-forth deliberation between Brownʼs team and security, the plan was set: utilize a car, circled by police members, to take Brown, his tour manager Alan Leeds, his promoter Bob Patton, his dancer Ann Norman, and his bodyguard and newly assigned driver James Pearson to the stage among a sea of dedicated supporters. In his book, There Was a Time: James Brown, The Chitlin Circuit, and Me, Leeds detailed the moment as a frighteningly rewarding experience.

Leeds said, “Inside the car, it sounded like a shell attack in a war movie. Pearson pointlessly shouted directions to Patton, Ann nervously clung to my arm, and James was cold silent…The boss never said a word, never displayed a hint of fear or concern.”

The police and security initially tried to keep fans away. But, the fans were too enamored with Isaac Hayes and his offerings to truly leave the field…

All worries completely ceased once Brown and his entourage joined his band, The J.B.ʼs, on stage and proceeded to give the audience all the signature elements from the “Hardest Working Man in Show Business.”

The call-and-response with famed band director and on-stage hypeman Bobby Byrd. The dramatic drop to the knees to convey command of the crowd. Shouts of “I want to get up and do my thang!” from the ultimate showman. Nonstop dancing while leading his own 21- piece band and balancing the machismo of “Sex Machine” with the romance of “Try Me” and never missing a beat.

The vibrancy and passion Brown gave to the crowd and his performance never gave anyone any inkling that he was fresh off a show in Tallahassee the previous night. New Orleans disc jockey legend, Soul Bowl ʼ70 talent agent, and show emcee Larry McKinley said in the publication, DATA the Amusement Guide, “Nobody else could have closed this show but James Brown… Itʼs unbelievable how these kids love him.”

After his final number, the showman thrust his clenched fist in the air – a fitting symbol of solidarity – as the audience shouted their approval in a chorus of “Right On, Right Ons” before Brown and his entourage jumped back in the car to depart the venue.

Jr. Walker: Put my toothbrush in my hand, and let me be a travelin’ man. Courtesy of University Archives, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University.

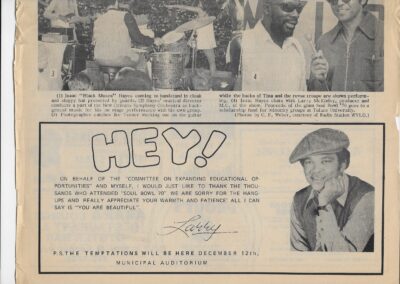

Soul Bowl ʼ70 was a success and the CEEO pulled off the unthinkable. But, the labors of their reward came at a cost. Delays caused the show to end at 9 p.m. – three hours later than its original intent. The show was able to avoid becoming uncontrollable and raucous like rock concerts of its time. However, a number of fans still endured a few cuts and scrapes due to frantic stage-rushers seeking a closer look at their favorite performers.

Numerous reports clashed over accurate attendance figures as some claimed that up to 40,000 were at the stadium. The Tulane Hullabaloo reported, in their November 6, 1970 issue, that only 26,000 were on hand and later declared, in their December 17, 1970 edition, that revenue only amounted to $130,000 – almost equaling the amount in underwriting to produce and deliver Soul Bowl ʼ70.

In spite of Soul Bowl ʼ70 not incurring any true financial loss, the attendance was not enough to generate great profit to refurbish scholarship funds as intended. Provost Deener responded that “funds for scholarships for disadvantaged students will be realized, however, through contributions to the Committee, particularly by some of those who had agreed to act as guarantors for the event.”

Tulane Hullabaloo: A one, a two, a helluva hullabaloo.

Questions lingered on what more couldʼve been accomplished to push Soul Bowl ʼ70 to greater heights. Could rumors of a race riot have been quelled much faster? Was a larger amount of support from more white students and locals needed? Why were only a limited number of tickets donated to charity? Did it need to include more jazz or entertainers tightrope walking between rock and soul?

Sadly, Soul Bowl ʼ70 was a one-time affair for music lovers, Tulane, and the city of New Orleans. The what ifʼs were plentiful, but a few results were positively undeniable. The CEEO not only delivered a lineup of megastars, in pursuit of a worthwhile endeavor, but also opened the universityʼs doors to plenty of Black and brown faces that maybe never thought Tulane could be their home for higher education.

Big wheels keep on turnin’. Proud Mary keeps on burnin’. Courtesy of University Archives, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University.

Big wheels keep on turnin’. Proud Mary keeps on burnin’. Courtesy of University Archives, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University.

Furthermore, in the same year as the inaugural Jazz Fest, one could argue that Soul Bowl ʼ70 further cemented the groundwork that can be seen in other New Orleans festival staples like Buku and Voodoo. Leeds stated in his book that Soul Bowl ʼ70 “was the largest [single-day] Black musical event until Wattstax in Los Angeles a few years later.”**

To this day, very few images exist of Soul Bowl ʼ70 with more consistent, documented commentary residing in past issues of The Tulane Hullabaloo and Tulaneʼs annual yearbook, the Jambalaya.

Video footage of the show on October 24, 1970, has yet to be uncovered by historians and music aficionados alike. However, the hope exists that footage will one day be brought to light to not only relish in the talents of the otherworldly performers but also celebrate each and every member of the CEEO.

With unsurmountable odds against them, the CEEO boldly took on the responsibility of the universityʼs administration and admission offices in the name of good will, true equity, inclusivity, and an even greater Tulane for the future. Their risk, efforts, and bravery truly embody the soul of Tulaneʼs motto: not for oneʼs self, but for oneʼs own.

Now, that…we can dig it!

Soul Bowl ’70 “was the largest [single-day] Black musical event until Wattstax in Los Angeles a few years later.”

–Alan Leeds

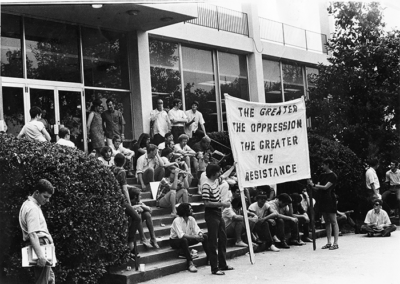

Tulane war demonstration

A tumultuous time for college campuses across the nation including Tulane University.

*Editorʼs Note – In 1970, Tulane Football ended their campaign with an 8-4 record and defeated Colorado in the Liberty Bowl with a score of 17-3. The “Year of the Green” was a success as the team finished their season ranked 17th in the final AP poll.

**Editorʼs Note – In 1969, a series of free concerts spanning over six weeks, known as the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, was held at Mount Morris Park (now known as Marcus Garvey Park) in Harlem, New York and drew over 300,000 fans. The Harlem Cultural Festival was headlined by artists such as Stevie Wonder, Mahalia Jackson, Nina Simone, the 5th Dimension, the Staples Singers, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Sly and the Family Stone, and more. Earlier this year, a documentary was released on the concert titled, Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised), that premiered first at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival and had a limited theatrical release before premiering on the streaming service Hulu in July.

In 1972, the city of Los Angeles hosted a single-day event called Wattstax led by Stax Records recording artists including Luther Ingram, Kim Weston, The Bar-Kays, The Staples Singers, Johnnie Taylor, and Isaac Hayes. Wattstax was created to commemorate the seventh anniversary of the 1965 Watts riots and was held at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. When representatives of Stax Records met with managers of the Coliseum, the Memphis-born record label was met with much apprehension that they could fill the venue. On August 20, 1970, 112,000 fans attended the show and it was marked as the largest gathering of African-Americans outside of a civil rights event to that date. Wattstax would not only live on as a recorded album but also a Golden Globe nominated documentary film in 1974. In 2020, the Library of Congress tapped the concert documentary for preservation in the National Film Registry as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

This story is not possible without the time and support of our outstanding contributors. I extend my deepest gratitude to the following for assistance in this feature:

Ann Case, University Archivist, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University

Rusty Constanza, University Photographer, Communications & Marketing, Tulane University

Jillian Cuellar, Director of Special Collections, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University

Alan Leeds

Hillary Lowry, Assistant Director, Office of Advancement, Tulane University

Christian McBride

Susan McCann, Digital Resources Coordinator, Communications & Marketing, Tulane University

Amy Morvant, Creative Director, Office of Advancement, Tulane University

Jennifer Navarre, Senior Research Associate, The Historic New Orleans Collection

The Tulane Hullabaloo

Lori Schexnayder, Research Services, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University

Melissa A. Weber, Curator, Hogan Archive of New Orleans Music and New Orleans Jazz, Tulane University Special Collections

Follow us on Social Media

Update Your Information

It only takes a moment to update your contact information and helps to ensure that you receive the latest news, exciting updates, invitations to events and more from Tulane University. Please update your most recent contact information by filling out the form below.