A QUEST TO REACH EVERY CHILD

Ellyn Ogden (NC ’82, PHTM *84): Fighting polio worldwide

by Mary Sparacello

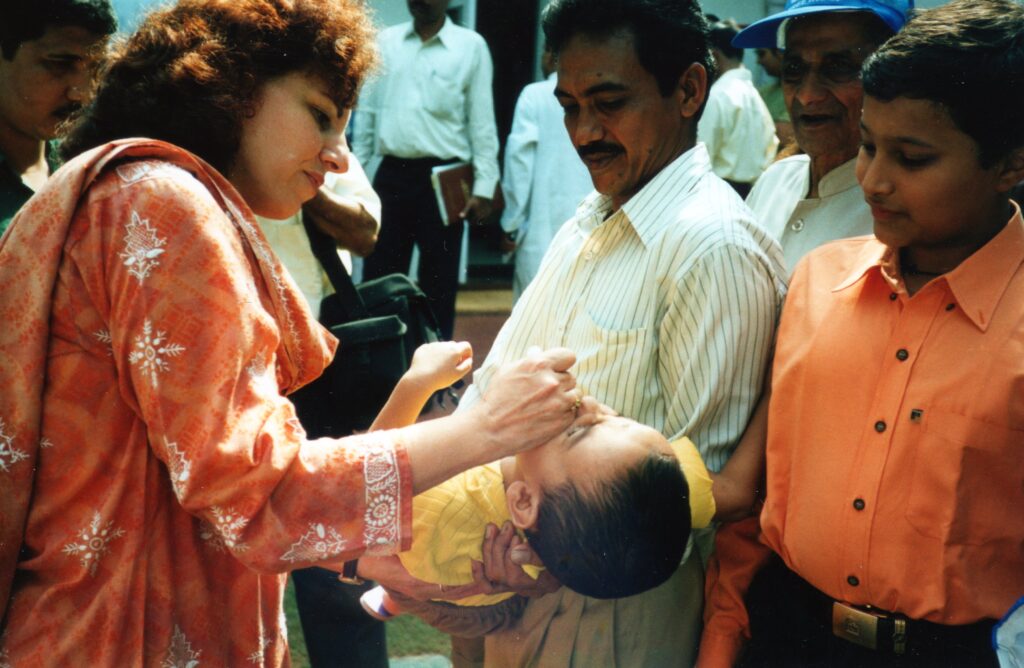

In Ellyn W. Ogden’s career in polio eradication, she has ventured to the most remote stretches of faraway countries, even entering warring nations to persuade rebel leaders to allow children to be vaccinated. It is all in her pursuit of vaccinating every last child against the devastating polio virus.

“It’s the willingness to go beyond where the road goes, to go to those furthest reaches, to try to find people,” says Ogden (NC ’82, PHTM *84).

As the worldwide polio eradication coordinator at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) since 1997, Ogden has travelled around the world vaccinating children. She has been instrumental in the fight to eradicate polio, one of the largest global vaccination efforts in history.

The massive success of polio vaccination – and the remaining challenges that are preventing global eradication – provide many lessons for COVID-19, Ogden says.

The polio virus is carried in feces and normally infects humans – mostly children – after they touch contaminated water or surfaces and touch their mouths. Polio causes no symptoms in most people, but in others, it can lead to paralysis or death when the virus attacks the brain and spinal cord. There is no cure for polio; the only way to combat it is through vaccination and prevention. Global polio eradication focuses on creating herd immunity by giving 7-to-10 doses of an oral vaccine to all children under age 5.

‘My ultimate dream job’

Ogden was born in Miami, but her family moved frequently for her father’s job with IBM. She knew from the time she was a small child that she wanted to work internationally and help combat diseases. “I was very inspired by smallpox eradication,” she says. Her childhood hero was D.A. Henderson, the American doctor credited with eradicating smallpox.

“For many years, I always thought I was going to be a doctor in the Peace Corps. So that’s sort of what I worked towards, even when I was very young,” Ogden says.

She was drawn to Tulane University by the prestigious reputation of the School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, known for its global work in infectious diseases. While she was an undergraduate student at Tulane working on her bachelor’s degrees in international relations and political science, she realized that instead of medical school, her calling was public health. She pivoted and pursued her Master of Public Health degree in international health and development from the School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine.

One of Ogden’s most significant impacts on polio eradication was negotiating with rebel leaders for ceasefires and “days of tranquility” in the Democratic Republic of Congo, to allow for millions of children to be vaccinated. She received USAID’s Award for Heroism in 2008 for her bravery.

Ogden put herself through school by working at East Jefferson General Hospital in Metairie, Louisiana. As an undergraduate student, she worked in the laboratory as a phlebotomist by drawing blood. In graduate school, she worked for the cardiology department. That experience proved helpful later in preparing her to deliver vaccines door-to-door in the polio program: “When you’re a phlebotomist coming up to people with a needle, you need to establish quick rapport at the bedside and make people feel comfortable.”

She met her husband, Neil R. P. Ogden (E ’80, G *85), in graduate school, and they jointly applied to the Peace Corps. They were assigned to Papua New Guinea, where she was put in charge of running a provincial disease control program. “I was working in remote areas, trying to (provide) health services with very limited resources,” Ogden says.

When Ogden returned to the United States in 1989, she started working for USAID. It was right at the start of the “child survival revolution,” an effort to reduce child mortality in the developing world. She was tapped to run USAID’s global polio eradication program when it began in 1997. It was “my ultimate dream job since I was 9 years old,” says Ogden. Since then, she has managed the disbursement of over $1 billion for polio eradication and helped oversee the vaccination of tens of millions of children.

“I travel 70 percent of the time,” says Ogden. “I monitor (vaccination) campaigns, I do surveillance reviews, I go to the far reaches of these countries. I listen to what women and men in communities are saying. You take a 360-degree look at it, and you often can come up with new, creative solutions to the problem.”

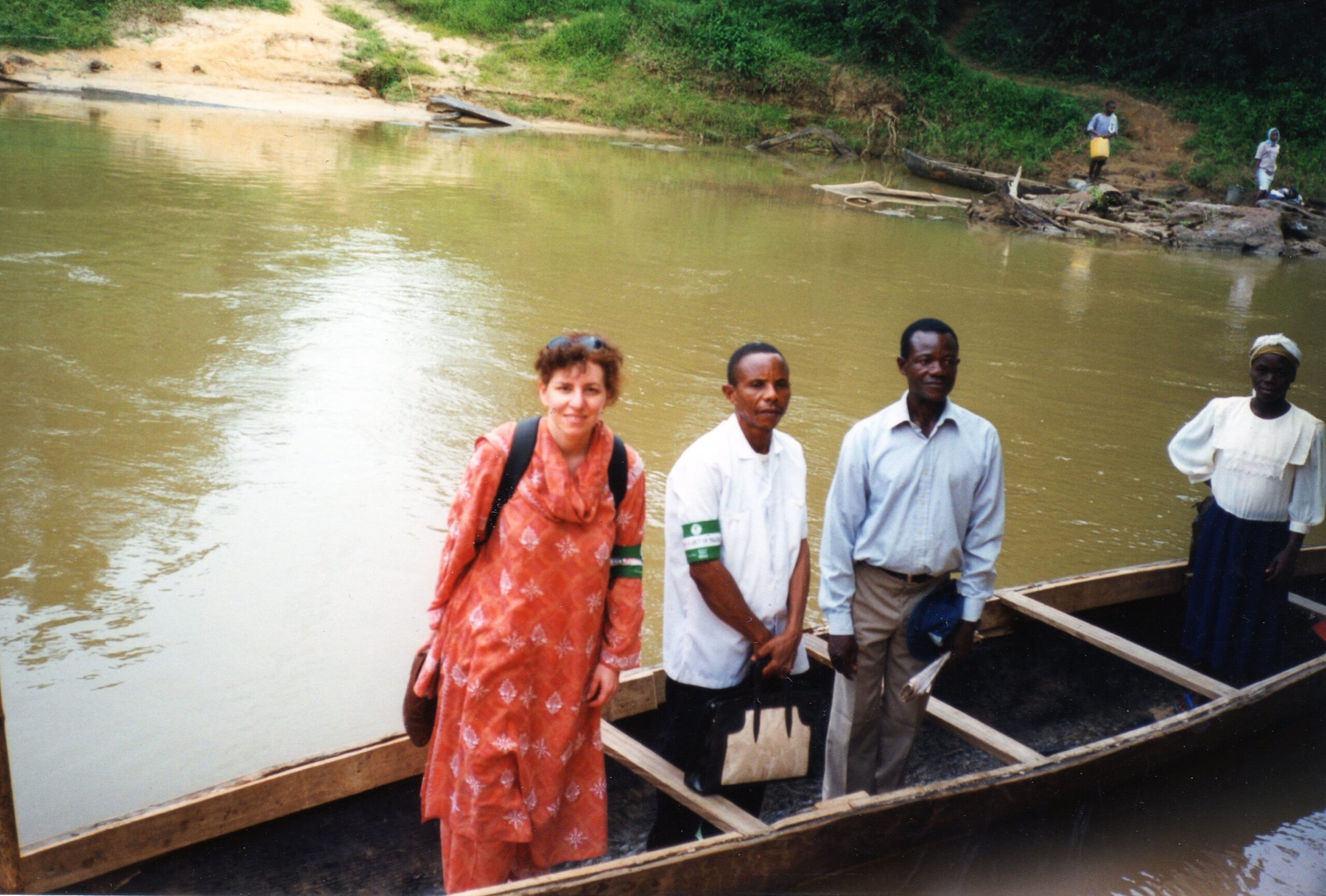

Going the distance to vaccinate every child: When Ellyn Ogden was monitoring the polio vaccination campaign in Nigeria, she ventured to the most isolated place possible, to check whether children there had been vaccinated. “We drove as far as the road would take us. And then we walked. And then we got to this river. And we had to call the canoe driver from across the river; he paddled us across and then we walked further. And then I had to walk across the ravine on a log bridge — like right out of Indiana Jones — then up this mountain to this remote community that harvests palm oil. And I got up there, and sure enough, the vaccination teams have been there, the markings were on the door, not just from this round, but previous rounds. The villagers could tell me the names of the vaccinators. And they hadn’t missed any children that we could find.”

When Ogden monitors vaccination campaigns, teams on the ground often plan her stay, picking a community for her to visit where children have already been vaccinated. To get the clearest picture possible, she often goes “not just beyond the road but off the road,” and that’s where she finds children who have been missed.

“I was once in Egypt, and we were driving through one directorate, and I saw children running around in a cemetery off to the side. And so, I asked the driver to stop,” Ogden remembers. “We went into the cemetery and started talking to the families and the children that were there. And what we learned is, these people have no homes, and they were living in the cemetery and nobody had come to vaccinate the children. They were not aware at all about the polio campaigns.” Ogden informed the polio teams for that area, and they added the cemetery to their vaccination plans.

In addition to vaccine hesitancy and hostile terrain, polio vaccinators also have to contend with how to inoculate children in war-torn areas. One of Ogden’s most significant impacts on polio eradication was negotiating with rebel leaders for ceasefires and “days of tranquility” in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

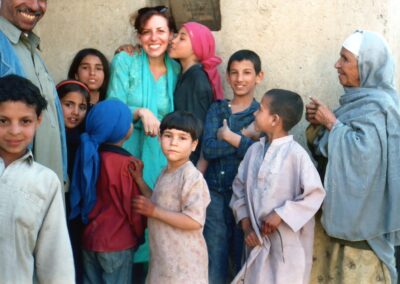

At the height of the war in Afghanistan, Ogden travelled to Helmand and Kandahar Provinces to listen and learn from the polio field teams and jointly identify solutions for vaccinating children living in the war zone.

“We knew we would not eradicate polio in the DRC unless we were able to reach all of the kids in the eastern part of the country,” Ogden explains. “So I was asked to go and see if I could broker an agreement between the main rebel forces in eastern DRC and get them to agree to allow polio campaigns to take place, (if) they would stop fighting for a few days and allow polio vaccinators to come and vaccinate.”

Her colleague in USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance connected her with these rebel groups in the city of Goma in DRC.

“And I shuttled between them and said exactly the same thing to everybody. And in the end, they all agreed,” she recalls. They hammered out the logistics in advance. “And so, on the agreed-on dates (about three or four days), they vaccinated six million kids.”

Ogden adds, “For the most part, ceasefires remained on the days of the (vaccination) campaign for more than 20 years.”

In addition to the DRC, Ogden has negotiated with armed groups in Angola and Afghanistan and many other regions, and she received USAID’s Award for Heroism in 2008 for her bravery.

Combatting a Gender Imbalance

When Ogden started her post in 1997, she was the highest-ranking woman in polio eradication, in terms of leadership and decision making and budget control. Three decades later, she still is. At the outset, she was surrounded by mostly men at leadership meetings, and most vaccinators were men.

She expounds on the importance of gender balance in polio vaccination by recounting her experience in a vaccine-resistant community in India. She went door to door accompanied by a male doctor to find out the reason for the hesitancy. “They were literally pounding on doors, saying ‘open up, let me in, we need to talk to you about your kids.’

No one answered.

“I spoke out, saying, ‘I’d like to talk to you about polio. Could someone come to the door? I’d just like to ask you some questions.’” The male translator relayed her words in a soft, gentle voice.

Finally, a grandmother slowly opened the door. “The women are not allowed to talk to men that are not family members,” says Ogden. “They can’t let people in the house. They had no information why the government was at their doorstep…We had to take time to talk to them, answer their questions, explain what we were doing. We got 200 kids vaccinated just because I spent half an hour answering their questions, explaining everything.”

Ogden says that after that experience, she advised that India switch to mainly female vaccinators.

“If you want to get into every nook and cranny and find every single child, you’re going to have to get a female workforce. Now it’s standard practice that most vaccinators are women. And they’re local and they’re known to the community. It’s not just gender balance. It’s that perspective that women bring about what are families thinking, about household decision making. When you’re only looking at it from one perspective, you’re missing some of the underlying reasons why we’re missing kids.”

Lessons for COVID-19

Ogden’s work has gotten the world closer to polio eradication. In 1988, when the global polio eradication effort took off, the disease was active in 125 countries, causing 400,000 cases a year. As of 2020, only two countries were endemic for wild poliovirus (Pakistan and Afghanistan) and there were less than 100 cases, Ogden says.

And Ogden hopes that her decades of hard work in fighting polio, the networks that she has built over the years, are going to help in working to bring an end to the current COVID-19 pandemic. “Polio has many, many lessons for COVID-19 … All of those networks and platforms that we established for polio, are now being utilized for COVID-19,” she says.

As a young child, Ogden was inspired by D.A. Henderson’s work in eradicating smallpox. And surely, someday, when polio is stamped out, young scientists will aspire to be like Ellyn Ogden.

It’s the willingness to go beyond where the road goes, to go to those furthest reaches.

Follow us on Social Media

Update Your Information

It only takes a moment to update your contact information and helps to ensure that you receive the latest news, exciting updates, invitations to events and more from Tulane University. Please update your most recent contact information by filling out the form below.